8th June 2024 - Villagers shared their memories of D-Day on the 80th Anniversary.

Presented by:

Maurelle d'Agostino, Mark d'Agostino, Vivienne Vellacott, James Dixon,

and guest Tom Ferguson

Script:

Colonel (Retired) Richard Vellacott OBE and Maurelle D'Agostino

Administration and Catering:

Olly and Roger Bramley

Soloist:

Maggie Caswell

Graphics:

Richard Vellacott

Read on for the text used:-

Mark

"We are here this evening to commemorate an amazing military operation - Operation Overlord - 80 years ago. Micheldever and the surrounding villages were like the rest of Britain, war-weary, tired of rationing, and all the deprivation war causes. On the national stage, plans were afoot for an invasion and liberation of France.

The Allied invasion of Normandy required a great air, sea and land force with military personnel from France, Norway, the US, Canada and Poland fighting alongside the British armed forces. It is hard to fully appreciate the sheer scale of Operation Overlord and the breadth of skills and people involved nearly 7000 vessels took part in D-Day, the largest amphibious invasion in history. The naval fleet delivered more than 130,000 troops to the Normandy beaches and it was enforced by 11,590 aircraft enabling 24,000 airborne troops to join the attack including daring parachute and glider landings.

It is hard for us now to understand how the planning was achieved. No E-mails or WhatsApp were available and absolute secrecy was vital for success.

Although a major turning point in the Second World War and fundamental to victory in 1945, D-Day and the battle for Normandy came at a high price. Around 210,000 Allied personnel were killed or wounded including 22,000 British and Commonwealth personnel who lost their lives.

However, our purpose this evening is not to dwell on the invasion and subsequent battle but rather on what had been going on around this area on pre-D-day."

James

Wartime.

"So war was declared on Germany on the 3rd of September 1939. From that time until the war ended in 1945 the civilian population were put on a war footing.

In May the home guard was established consisting of those men who were excused from military service because of age or reserved occupations such as farming. The local HQ was on the A30 East of Sutton Scotney at the Wonston /Norton crossroads at what is now known as Kitson’s clump.

Did you know that Micheldever church was guarded each night? Malcolm Hallam’s Dad who was in the Home Guard was allowed the first shift as he was a cowman and had to get up early to milk the cows."

Mark

"The Home Guard did a valuable job. On top of their day job, they had to spend a considerable amount of time in training but upon occasion, there were some” Dad’s Army moments. I recall my grandfather, a farmer, telling me that as a member of the Home Guard, he used to cycle down to another farm to meet up with a farmer at night as it was their nighttime duty to guard a little railway station. My grandfather’s friend was quite fond of his bed and it was my grandfather’s duty to wake him up. Whilst waiting for his friend to get ready Grandfather settled down by the warm range. It had been a busy day, Grandfather felt sleepy in the warmth and he fell asleep. His friend kept sleeping. Needless to say, the railway station wasn’t guarded that night.

On another occasion, the Home Guard were on parade. The farm dog insisted on joining the parade much to my Grandfather’s embarrassment.

As able men were all at war there was a shortage of labour for farm work so women were employed, numbers reaching a peak in 1943. The Women’s Land Army were paid 28 shillings per week by the farmer and the land girls had to pay 14 shillings for board and lodgings. That is £1.40 for a 48-hour week and 70 pence of that for board and lodgings."

Vivienne

"Blackout regulations in the villages around here were strictly enforced by the local constables and special constables.

Rationing was introduced and everyone was worried about how they would be able to cope. This encouraged widespread bartering. The quality of flour was appalling but the bakers succeeded in meeting demand and making it appetizing. In this farming community, nothing went to waste.

However, Micheldever and the surrounding agricultural villages possibly felt the rationing less than in towns.

Here there were flourishing allotments and gardens to provide fruit and Vegetables. Hens would have been kept for eggs or meat and the occasional rabbit would have found its way into the cooking pot.

Householders were allowed to keep 2 pigs but they had to sell one to the Ministry of Agriculture Francis Hitchings, who was 10 at the time, still lives in Micheldever and tells us that he can’t remember being short of food.

Everybody knew each other and possibly many were related so there would have been a good support system for those needing help."

Maurelle

"In the summer of 1940, the Luftwaffe started their massive aerial bombardment of the cities in Southern England which included Portsmouth and Southampton. Children and their mothers were evacuated to country areas across the UK and some were housed with local families in the Dever Valley.

One such family was that of Anthony George Purnell who was born in 1939. His family home in Southampton was badly damaged by a German landmine in the early 1940 and alternative accommodation had to be found. He finally ended up at Plough cottage in East Stratton with his Grandparents - George and Pricilla Griffin. He was a gamekeeper at Northington. - Plough Cottage.

Just after the war, houses in Stratton Close were built by the Rural District Council, and first refusal was given to those who had served in the war. Anthony's father with his son had served in France as a dispatch rider with the Somerset Light Infantry and he was one of those chosen. The family moved into 6 Stratton Close in 1946 where he still lives to this day.

Often the villages of the Dever Valley and Winchester were used as aerial turning points if the anti-aircraft fire was too intense over the cities. Consequently, the odd bomb or stick of bombs could catch the unwary out.

Geoffrey Whitear, who lived in the village for most of his life remembered sitting on the handlebars of his father's bike coming home from the Doctor at Wonston. He had stuck a ball bearing in his ear! He was blown off the bike when one such bomb exploded at Weston Arch, the blast sending them both falling into the ditch.

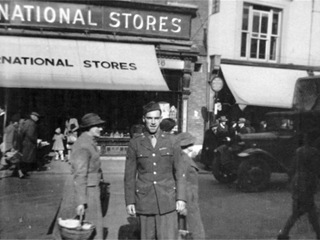

These raids continued into 1943. One such raid where the pilot did not want to fly home with his bombs still on board was responsible for the death of one of the names on Micheldever’s War Memorial. 26-year-old Doris May Lay was the only child of Albert and Ruth Lee of Micheldever Station. She had volunteered to join the National Fire Service as a firewoman and was waiting with others for a special bus in Hyde Street, Winchester to take them to the venue for their first day of training.

A bomb from a low-flying German aircraft exploded in a row of shops and cottages on the west side of Hyde Street (Photo 5) killing seven people, including Doris Lay,). The youngest casualty that day was a girl age just 12 on her way to school. It started to rain and she went back to get her raincoat."

Mark

"So what else developed in this immediate area over the period 1939 to 1944?"

Vivienne

"Worthy Down camp was a naval air Station known as HMS Kestrel. This became the main centre for Spitfire development and test-flying operations. here you see a Lysander aircraft, used for training pilots. On the right of the three pilots is the late Sir Laurence Olivier, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

Jo Vellacott, the late aunt of my husband (Photo 7) Richard, served there in a more lowly capacity in the latter part of the war as a naval air mechanic, having joined the WRENS straight from school at the age of 18.

When Spitfire test flying finished in 1944, Worthy Down played an important role in the logistics support for the D-Day landings Spitfires needed a sizable spare backup. On Hunton Lane, close to Wonston, Vickers built an 808 m² store which carried the small spares and parts for Spitfires. It was used throughout the war until October 1946."

Mark

Micheldever.

"A dummy airfield was built to the south of the village, near Bazeley Wood. This was a decoy site to attract enemy bombers away from Worthy Down. The real air station was heavily defended with a ring of 32 pillboxes and trenches, which were manned on occasions by a battalion of regular infantry, led at one time by Lionel, Lord Tennyson, grandson of the famous poet and former captain of Hampshire cricket club.

Those of you who remember Ernie Hobbs, another long-time resident of Micheldever, told how he and others went up to the dummy airfield regularly to light flares to act as a decoy. There is still a bunker there now.

I remember Ernie telling me that on D-day he was building Coles barns which was a series of black Nissen huts at the time and now have been replaced by the big grain barns on Winchester Road. He said that he and his co-workers rushed home to hear about the invasion on the wireless"

James

Micheldever Station.

"At the beginning of the war, the Air Ministry decided to build a fuel storage facility at Micheldever Station, one of a series away from the coast and therefore less vulnerable to bombing by the Luftwaffe. The terminal supplied fuel to nearby aerodromes. The facility had a storage capacity of 18,000 gallons. The storage tanks, which were protected by anti-aircraft guns and searchlights escaped any bombing.

In 1943 an ordnance emergency depot was built, together with 17 sidings, at the station. The depot was affectionately known as Woolworths - it could supply everything needed by the armies overseas from a nut to an engine for a tank. In the days leading up to D-Day, 1000 railway wagons a day were being handled at Micheldever station. The depot was staffed by upwards of 1000 soldiers."

Maurelle

Popham

What would happen if the U.K.’s prison population suddenly increased by 400,000 people? That’s what occurred between 1939 and 1948 when thousands of Germans, Italians, Ukrainians, and others became Britain’s prisoners of war.

The camps where the POWs were imprisoned have largely, but not wholly disappeared. At one time hundreds of them were spread across the UK. The well-researched book titled ‘Churchill’s Unexpected Guests by Sophie Jackson covers all the POW camps in the UK. She asserts that there was a POW camp at Popham, known as Popham camp, and provides photographic evidence to support her view. This suggests that the local gossip that there was a camp in the Western Farm area above the Micheldever Station site may be wrong. Probably, the remains of buildings in this area were created for the staff manning the Ordnance Depot."

James

"Clive Dixon, about whom you will hear more, remembers that the prisoners were Italian and they were used on the farms in the area.

My father had an Italian prisoner of war (Photo 12) living on our farm. My recollections are hazy as I was a very very small person then, but I had the impression that he lived almost as one of the family. They had to report to the local camp every Sunday and he frequently took me. I got my hair cut there and was given toys that the prisoners had made and Franco made ice cream for us using jam as the sweetener and snow as the freezing agent."

Mark

Sutton Scotney.

"A secret military engineering branch of the War Office was based at Moody Down Farm just to the West of Sutton Scotney off the A30

They were responsible for the research design and subsequent use of FIDO Fog Investigation Dispersal Operation which was developed to clear fog from Aerodromes and for PLUTO the Pipe Line Under The Ocean. This was developed to move fuel to the Normandy beaches by an undersea pipeline and became operational two months after D-Day. (PLUTO - video 1).

Establishing mobile filling stations that advanced with the military was superior to the German method of using petrol cans. However, the German petrol cans were superior to ours as they stacked and ours didn’t. Hence we now have JERRY Cans.

Vivienne

The arrival of the Americans.

"There was a huge build-up of troops before the D-Day period. Some 18,000 troops were stationed at Barton Stacey camp. Initially, Canadians used this camp but from late November 1943, men of the 9th US Infantry Division started to arrive in England having fought in North Africa and Sicily. The Divisional Headquarters moved into Northington Grange (Photo13) then viable living accommodation - with the 3 Regiments setting up shop in Bushfield Camp Winchester, The Dene in Alresford, some in the Basingstoke area and Barton Stacey Camp.

Troops would alight from trains at Sutton Scotney station and march to the camp headed by an enormous brass band. Tanks and armoured vehicles were generally moved by night and assembled on the barrack square. The Garrison Theatre was in constant use seating over 1000 men. Some residents were privileged to attend a live concert there by Glenn Miller and his band.

Once the preliminaries of getting the troops billeted into the various camps were completed, the men were anxious to explore the countryside and meet the local folk. However, before being allowed to leave camp and fraternise with the residents passes were issued.

Free time was only the beginning of the pleasures. The troops appreciated the local hospitality and in towns and villages the pubs became their local. They explored the countryside on hired bicycles, dances were organised and held on Saturday nights at village halls and in many places in Winchester.

A bus collected all the young girls from Micheldever and took them to the various halls in the area. The mayor of Winchester allowed cinemas to open on Sundays. It is true to say that the Americans made a huge impact on this area.

Jill Whitear again a lifelong resident of Micheldever remembers playing in the garden when a truck drew up and the driver asked directions to the pub. Jill looked up and ran to her mother as if she had had such a fright. The driver was a black man and she had never seen one before."

Mark

"It was inevitable that romance would blossom between our local girls and the Americans and we have the poignant story of Alma and Delbert."

Maurelle

"One of Baring’s Bank employees went with her younger sister Alma on holiday somewhere in the West Country. In the meantime, Barings Bank had moved from London to Stratton Park for safety. The girls received a telegram from their mother telling them not to come back to their home in London but to go to a village called East Stratton in Hampshire as the bank had decentralised.

Both sisters and their mother settled to live in East Stratton. One day, whilst working in the garden Alma, was approached by 2 American soldiers who had walked from their camp to the pub. It was closed so they asked Alma when it would open again. She told them “Not for another 2 hours but come in and have a cup of tea. My mother loves entertaining and she will be pleased to see you".

This was one of many visits made by one of the soldiers, Delbert, to that house. Alma and Delbert fell in love and eventually sought the permission of his commanding officer to marry. Sadly, this permission was refused as those in authority knew that an invasion was imminent and America didn’t want a lot of war widows.

Delbert tried to get in touch with Alma before he left for France but she was unable to get to Winchester railway station before he left. That was the last communication Alma had with her fiancée as he was killed 2 or 3 days after D-Day (Photo 16).

After the war, Alma went to America to meet Delbert’s parents and she kept in touch with them until their deaths. And what of Alma? She became a land girl but she injured her back lifting heavy buckets of swill over the pig-sty walls She was allocated lighter duties and became a rat catcher with Bob Brown, a gamekeeper. Alma subsequently trained as a teacher. She settled in Micheldever marrying Bob Brown, a widower and her erstwhile boss and together they had a son Robin.

James

"The way of life in the quaint buildings, the cottages and family-owned shops in and around Winchester fascinated the Americans. They marvelled at the peaceful countryside and the friendly character of the people. Driving on the left-hand side of the road soon became natural.

Christmas 1943 was a much happier period. The men organised parties for the children and Father Christmas handed out gifts generously donated by the men. With Christmas celebrations over the troops settled down to training, ever mindful of the real task which lay ahead.

On 19 January 1944 General Montgomery (Photo 18) made a personal appearance to see the men of the 9th Division. He addressed them and reminded them of the old days of the battles in North Africa and Sicily, He did not indicate where or when their next assignment would be.

When the damp winter weather turned into crisp spring, training stepped up and talk of the invasion was becoming more prevalent. By now there were so many jeeps and half-track vehicles hidden in the woods on the Northington estate that it necessitated organising a one-way system; so the troops built a road from Northington Grange to East Stratton."

Maurelle

"On 24 March 1944, Winston Churchill and the Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower arrived in Winchester.

They visited various US campsites, together with General Omar Bradley who was the Commander of the First United States Army of which the 9th Division was part. Here they are in Bushfield Camp, Winchester and in Barton Stacey Camp.

After visiting the troops Winston Churchill, with Eisenhower and Bradley, met at Northington Grange for about three hours. Shortly after this visit, all leave was cancelled. It was then that the men knew their stay in Hampshire was going to end soon.

As the military buildup continued the road between Hill Farm crossroads and Three Maids Hill on the outskirts of Winchester was closed and turned into a huge garage to maintain the masses of vehicles in the area. Sheds were even erected over the road to provide cover. Winchester Bypass Road also became a "parking lot"

James

"Before D-Day troops in convoy of vehicles bumper-to-bumper lined the road through Sutton Scotney on their way to Southampton. The convoy travelled at 50 mph with 6m between vehicles. The Americans would throw peanuts and chewing gum out of the lorries to the villagers who waved to them, wishing them well. only too aware of where they were being sent.

On the 5th of June 1944, some 2000 Sherman tanks passed through Sutton Scotney, travelling at night with very little light showing, keeping the villagers awake. Francis Hitchings recalls lorries being parked under the trees at Cowdown and the Americans giving the curious children sweets."

Mark

Let's turn now to what happened on the night of 5 June 1944. Keep a look out for John Tillett who was a long-time resident of Micheldever and was the father of Anthony Tillett who many of you will know.

John was one of the 180 men who took off from an airfield in Dorset in 6 Horsa gliders late on the evening of 5 June 1944. Their task was to capture Benouville Bridge, now known as Pegasus Bridge and another bridge nearby."

Let's look at a video about the attack on Pegasus Bridge. (Video 2)

Richard

John Tillett was in the company led by Major John Howard, who landed by glider at 2100 hours on 6 June 1944 to capture two vital bridges in Normandy, of which one was Pegasus Bridge, near Ranville

John was actually in the second wave of gliders. He remarked that the first group thought that they had a tough task when they caught the Germans off guard. The reception for the second wave, when the Germans were awake was something different.

He was a regular visitor to the annual pilgrimages to the D-Day beaches and Pegasus Bridge. As a mark of the respect in which John Tillett was held, the late Field Marshall, Lord Brammall attended his funeral in this church.

He lived in the Old Post Office in Church Street and his later years in Brook View Northbrook. He died in December 2014 and his grave is in the churchyard. This view of Pegasus Bridge was taken after being tidied up after the fighting and you can still see one of the gliders in the background."

Mark

Now to D Day 6th June.

"What were the thoughts of those soldiers on the move? Maybe some re-read letters from wives or sweethearts, some may have written letters home., whilst some may have written letters only to be delivered if they were killed.

Here are some extracts from those letters

Vivienne

Major Rodney Maude in command of 246 Field Company, Royal Engineers. Landed on Sword Beach on D-day June 4 1944.

"My dear Mum,

You certainly won't get this letter until after the event, as it were, but I hope it won't be delayed too long. I am writing this on board the ship in which we go across. At the moment, of course, we are at anchor off the coast of England, surrounded by a great many other ships and craft.

We embarked yesterday afternoon. We had lunch in camp and then got into buses and drove - very slowly - down to the harbour. The men were all very cheerful, cracking jokes and cheering every girl we passed on the way. You would never have dreamed, except for the amount of equipment we were carrying, that we were not going on another exercise. I must say I didn't feel any different myself.

I have known for over a year of course that we would eventually go off on this, or something similar, and I used to dread the last preparations and the final parting from friends and England, but in actual fact (fortunately) I haven't minded at all, now that it is really happening. We all feel very confident and optimistic about the result of the landings, and we all think it is going to be a walkover - at first, anyway.

Also, it simply doesn't occur to anyone as a possibility that anything unpleasant can possibly happen - to other people, yes, but not to oneself, so naturally nobody worries about it. And also we are all intensely interested to see how this thing which we have been planning so long and training for so long does work out in practice. I hope you have been getting some of my letters, but I am afraid they haven't been very good ones recently for obvious reasons - and there probably won't be any more for some time as I shall be rather busy for a few days! Anyway, please don't worry, I am sure to be all right and no news is good news. All my love to you, and don't worry.

Your loving

Rodney

(Major Maude survived the war)"

Richard

Lieutenant H T Bone of the 2nd Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment, to his mother July 4 1944.

"Apart from our ordinary equipment, we were loaded down with heavy packs, a pick or shovel each, 24 hours' rations, ammunition and maps.

And further on …..

As we staggered ashore, we dispersed and lay down above the water's edge. Stuff was falling pretty close to us and although I did not see it happen, quite a number of the people from my own boat were hit. Instinctively, where we lay we hacked holes with our shovels. I began to recognise wounded men of the assault companies. Some were dead, others struggling to crawl out of the water because the tide was rising very rapidly. We could not help them since our job was to push on, but I saw one of my signal corporals with a wound in his leg and I took his codes with me promising to send a man back for his wireless set before he was evacuated.

Your loving son

etc

Lt Bone survived the war."

Vivienne

2nd Lieutenant John Lundberg US Army May 19

"Dear Mom, Pop and family,

Now that I am actually here I see that the chances of my returning to all of you are quite slim, therefore I want to write this letter now while I am yet able.

I want you to know how much I love each of you. You mean everything to me and it is the realisation of your love that gives me the courage to continue. Mom and Pop - we have caused you innumerable hardships and sacrifices - sacrifices which you both made readily and gladly that we might get more from life.

I have always determined to show my appreciation to you by enabling you both to have more of the pleasures of life - but this war has prevented my doing so for the past three years. If you receive this letter I shall be unable to fulfil my desires, for I have requested that this letter be forwarded only in the event I do not return.

We of the United States have something to fight for - never more fully have I realised that. There just is no other country with comparable wealth, advancement or standard of living. The USA is worth a sacrifice!

Remember always that I love you each most fervently and I am proud of you. Consider, Mary, my wife, as having taken my place in the family circle and watch over each other.

Love to my family"

John Lundberg was killed in action two-and-a-half weeks after D-day, aged 25."

Mark

"Let’s now have a look at some contemporary Films of the sea crossing and some of the leaders behind Operation Overlord.

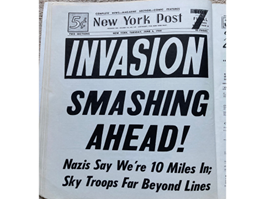

And of course, the newspapers picked up the story. This is the New Yorker headline, and the Evening Standard picked up the story.

So now let’s look at a photo of the landings at SWORD and JUNO

We have a link to SWORD Beach through our next vignette

Maurelle

Colleen Stainer, who lives in the village, tells us her father, Reginald Martin was a bandmaster on HMS Frobisher which was bound for Sword Beach.

Their job was to draw fire from a battery at Ouistreham. Bandsmen were below decks in the gunnery control room. However, Reginald asked and was permitted to go up on deck. On being asked what he saw he replied,” Bodies, Bodies everywhere”. The next day they went ashore with their instruments to play for the troops to raise morale.

Mark

Maggie sang A E Houseman’s poem Is My Team Ploughing.

Although the words were written after the First World War it is still appropriate for the Second World War. The poem tells of a dead soldier asking his friend if his horse team is still ploughing, how his football team is faring and how his girlfriend is. She is now the wife of his friend

What was happening in France? We are now going to see a short film made by my two nieces and a friend who live in France - Eliza and her Video (Video 3) filmed in France.

Let’s hear the memories of a private soldier from East Stratton who landed in the second wave on GOLD beach as told by his grandson Tom Ferguson."

Tom

Private Fred Messenger. Enlisted 15 July 1943. Discharged 15 July 1947 Fred was called up in Bradley while working on the poultry farm. He spent an initial six months as part of the Home Guard where he trained for the potential German invasion alongside men whose ages ranged from under 18’s up to those in their 90s. He reflected that they had trained with hay forks, ill-fitting uniforms and had one rifle between two men with very little ammunition.

Fred’s training took place all over Britain and included Colchester, Axford, Moundsmere Manor, Blackburn, Southwold, Inverary, Glasgow, Leigh on Sea and Beaulieu Road. This training became increasingly intense with marches initially being 25 miles, building up to 75 miles across the moors of Lancashire.

Fred went through toughening-up courses before then officially joining the 1st Battalion The Hampshire Regiment. His battalion was inspected by the King whilst in Southwold but Fred missed this as he had been assigned to “spud bashing” duty, i.e. peeling potatoes!

Fred took part in multiple mock landings whilst based in Southampton before he embarked on a boat for France. "We would get changed and then go again, it was bloody cold” he reported.

During the hours before the invasion, Fred spoke of how whilst dealing with seasickness and thoughts of not knowing what to expect when he arrived at the beach. Small frustrations like "all my fags were wet through" had more significance. After having to cope with a rough sea in a small landing craft, wearing a full kit weighed down further with his weapon, sten gun ammunition and a ladder, Fred describes his experience of his landing at Gold Beach heading towards Arromanches.

"1st wave of the landing went ahead of us and we followed in behind them, the 2nd wave coming through. I had a white tape and my job was to run up the beach and lay the white tape for people to run up after I’d gone through. The terrible thing was to see people dead and wounded and you can't do anything about it because you have to keep moving. That was horrible. There was a hell a lot hell of a lot of fire going on”.

Fred was able to move inland after naval guns had bombed German bunkers just off the beach. Despite the terrible things he witnessed, Fred described how impressive elements of the spectacle were. "That night, oh it was beautiful. All the tracer bullets going through the air you know... you see all these lights. It was absolutely beautiful. Wonderful firework display it would've been."

Over the next few weeks, Fred fought in hastily dug trenches as they moved forward bit by bit. He took part in the ‘hedgerow warfare” from field to field and wood to wood where shelling and snipers were a constant threat. "It was scary knowing that someone might be creeping up on you all the time"

Fred was part of the liberation of Bayeux before being wounded by ‘friendly fire ’while he was guarding a wall. A communication error led to him and his friend not being relieved and the relief team mistook them for Germans and opened fire. He was wounded by five bullets in the wrist, hip and both knees.

After being evacuated to a field hospital he recalled that the doctor said "Let's see the mess they made of you mate. What have you got in your pocket?” I said "Oh it's a grenade”. He said "Oh God what am I gonna do with it!" Fred replied, "if you hold it I'll pull the pin out”. The doctor took a moment before asking him .....” are you sure about this?”. I said, “Well if I'm not then we will both go up".

They then proceeded to defuse it between them.

Fred was evacuated back to England and various hospitals where he spent time convalescing. He expected to go back to France but his wounds proved too serious and he spent the rest of the war

guarding German prisoners in the UK and Germany. This included high-ranking officers. He even managed a cinema.

Fred preferred to focus on memories that made him chuckle. These included tales of climbing through hospital windows after arriving back after curfew, dodging the matron when gambling, being terrified by his first ever train journey, falling asleep on a bottle of whiskey and hurting his back, eating REAL eggs when he was in an American camp and the curious tale of an unexpected encounter of a German and British patrol who surrendered to each other!

Fred's perspective on his time in the army was that "I was scared all the time, but I said my prayers and they were answered”. He concluded that those that fought did so for the rest of the men that they were fighting alongside.

My grandad was the gentlest person I've ever known. He did not speak of what he was a part of until my other grandfather asked me if he done more than he had let on. I was around 10 at the time and listened to all. He has been one of the most significant influences in my life and I'm so very proud of him and of those who gave so much

Mark

"Two other people who came from this village were directly involved in one way or another in the landings in Normandy.

The first is Vice Admiral Sir Norman Denning was a naval Commander at the Admiralty throughout the War and served as Director of Naval planning from 1945 to 1956. He is credited with playing a major part in the planning for D-Day, managing aerial photo intelligence in particular.

After his retirement, he was a churchwarden of this church and there is a plaque over there in his memory marking his significant achievements during World War II. He lived in Rose Cottage in Duke Street where he died in 1979. His grave is in the churchyard.

I now call on James to speak about his father Clive Dixon

James

My father, Clive Dixon, was born in 1924 and came to live in Micheldever Station in 1927 at the age of 3. So when war was declared he was just 15. Towards the end of his time at school, a visiting army general made a huge impression on the Upper Sixth boys. This was 1942 and the War was far from won and they were all left in no doubt as to where their duty lay. They needed little encouragement, and on reaching the age of 18 Dad signed up to join the army.

A very rushed 6-month officer training course then followed at Sandhurst before Dad joined his regiment of the 24th Lancers, an armoured cavalry regiment, formed in 1940, as a second lieutenant.

Posted initially to Bridlington in Yorkshire it wasn’t long before the regiment found itself heading for Southampton as part of the the 8th Armoured Brigade, part of the Normandy invasion force. On their way there he found himself stopped for the night on the A33, right at the end of Larkwhistle Farm Road. Annoyingly he wasn’t allowed to travel the mile and a half to see his parents!

On the night of June 5th, their ship carrying them, and their Sherman tanks set off and they then spent a very rough, anxious and uncomfortable 36 hours being tossed around in the channel and then moored 3 miles off the French coast being shelled by German artillery, waiting for their time to land on Gold Beach. It was at this time that the enormity of the task that lay ahead, together with the responsibility that a 19-year-old inevitably felt towards the 14 men under his command, combined to have a huge and lasting effect on him.

By D-Day +1, landing on the beach was unopposed but this quickly all changed on day two when the enemy was encountered. It quickly became obvious to Dad that it was almost a case of men against boys and that they were up against a vastly superior and more experienced enemy.

A journal, later published as a book, was kept by the regimental Doctor. One revealing insight says so much and reads “… I looked around at the weary men who only a few days earlier had presented as fresh-faced youths. They all appeared to have aged by 20 years in this short space of time.”

Dad’s luck ran out after 6 days of fierce fighting when he was seriously wounded whilst under enemy fire.

The same Doctor wrote…” Two casualties were brought to me, Clive Dixon and Kenneth Wareham, both bad. I quickly realised that there was little I could do for them here and sent them back to the main field hospital. Poor Dixon’s hand is almost off and I doubt it can be saved.” It was June 12th, the day before his 20th birthday.

The 24th Lancers was disbanded a month later having lost so many officers and men, it was unable to function as an effective fighting unit.

Dad was repatriated after recovering sufficiently to travel. At that time, there were expected to be many thousands of casualties being shipped back to the UK, and it was decided to fill up the British hospitals starting in the North of the Country and then progressively further south as more and more arrived. Dad was sent to Carlisle Hospital where his arm became gangrenous and had to be amputated. He was invalided out of the army in July 1944

Back at home he joined the Home Guard and continued to live in Micheldever until his death at the age of 96 in 2021. "

Mark

Some were less fortunate than John, Fred, Sir Norman and Clive. Their names are on the Micheldever War Memorial

Vivienne.

Second World War names from the War Memorial. Click here for full details.

Ludovic Brandt, presumed missing flying a Stirling Bomber that crashed into the North Sea in 1942 aged 30.

Doris Lay, Firewoman, National Fire Service from Micheldever Station, died Winchester 1943 aged 26.

Arthur Mansbridge of Micheldever, died in 1945 aged 31. Buried in Suez War Memorial Cemetery.

Sydney Dennis Slocombe of Micheldever, died in 1940 aged 29. Buried just outside here opposite the door of this Church.

Donald Smith of Micheldever, died in 1944 aged 20. Buried in Cesena War Cemetery Italy.

William Stratton of Micheldever, died 1942 aged 31. No known grave but commemorated on Rangoon Memorial, Myanmar.

Arthur Whitear died 1941 aged 25 buried in Damerham Hampshire. Arthur Whitear was an uncle of Geoffrey Whitear, he with the ball bearing in his ear, and was in the Army and on guard duty in this country. He swapped duties with his friend but unfortunately, a bomb fell and he was killed.

and East and West Stratton WW2 names, from East Stratton War Memorial.

CHARLES EDWIN COFFIN, Private, Army Catering Corps, attached 4th Battalion The Wiltshire Regiment, died in France on the 2nd July 1944, age 38.

EDWARD LAISHLEY, Gunner, 132 (The Glamorgan Yeomanry) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, died in North Africa on the 27th November 1942, age 19.

CHARLES ARTHUR SMITH, Guardsman, Scots Guards, died in The Netherlands, on the 23rd September 1944, age 31.

ALMARIC BRUCE WILSON, Second Lieutenant, 15th/19th The King's Royal Hussars, Royal Armoured Corps, died The Netherlands, on the19th October 1944, age 19.

We do not forget those named on the Sutton Scotney Memorial (Photo 39) but time precludes showing their names.

Mark

Conclusion

"Sitting here in this place in peace it is difficult to comprehend the level of bravery shown in so many ways by so many people. We were told by Robert Winnall about his grandfather, a Royal Marine, who arrived on 7th June on one of the beaches in a landing craft. Bullets were hitting the ramp before he disembarked. What courage to get out of the landing craft. He told Robert that the beach was littered with bodies, a scene that probably never left his mind."

Maurelle

"At home, clothing was rationed as fabric was needed elsewhere for uniforms. But make-do and mend clubs soon sprouted and new clothes were made from old. Rationing encouraged individual ingenuity and creativity. I was told that I had a party dress made out of a velvet cushion cover Such is the resilience of the human race. Despite rationing, deprivation and fear there was still a life to be led. The entertainment industry helped in this regard keeping morale up. At the end of the war on VE Day, Jill Whitear remembers a piano being lifted onto a trailer and it being towed around the village, the pianist playing all the popular songs of the day.

Vera Lynn's songs were very popular.

To end we would like you to join our very own SUPREMES for a couple of her songs and as Rob would say please sing brilliantly. Accuracy isn’t so important.

White Cliffs of Dover

We'll meet again.

National anthem.

Lest we forget Rev'd Rob Rees' closing remarks

The Nave -

with wartime food by Olly and Maurelle - spam, marmite, cheese and chutney, egg and tomato sandwiches; rock cakes, a wartime fruit cake, and strawberry jam tarts.

Afternotes

The Church - see /history/st-mary's-church

Harry Symes. His memorial seat is just outside the doors of the Church. During the War, church bells were not allowed to be rung except as warning of invasion. By 1944/45 most villages’ bells were stuck, but Harry Symes, of the notable village blacksmith family, had greased and eased ours frequently so they were one of the few that could be sounded.

Sydney Dennis Slocombe noted in the Presentation as on the War Memorial and buried in the Churchyard, in the late 1930s flew a Spitfire under the Winchester- Alresford road bridge on the then new bypass, hence it being known as 'Spitfire Bridge'.

A great evening and very informative.